Chapter 3 Decision Trees

3.1 Tree Structure and the Classification Task

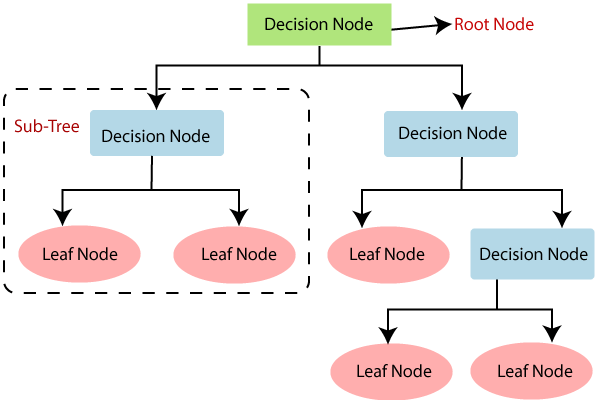

We’ve found that Random Forests provide an excellent basis for elucidating the role of certain SNPs in relation to inferring local ancestry. Before diving into random forests, we will discuss their building blocks: decision trees. Within the context of inferring local ancestry, we want to figure out how to categorize a certain part of an individual’s genome using predictors, which in this case are our genetic variants, SNPs. Below is a decision tree, labeled with its general components.

Figure 4: This depicts the basic structure of a decision tree. (Source: https://www.javatpoint.com/machine-learning-decision-tree-classification-algorithm)

Our first initial node, or the root node, essentially takes our most influential predictor and classifies our data into subsets for the subsequent decision nodes. Each split in the data made at each decision node is representative of regions in the predictor space. That is, each split on a predictor results in regions of the predictor space. Each following decision node is made up of the next best predictive parameters. At the end of each decision node, the classification tree makes its prediction at the leaf nodes. In general, the strategy of a classification tree is to continuously split the data into subsets or regions based on predictor values until the regions are uniform in their outcomes.

3.2 Classification Tree Example

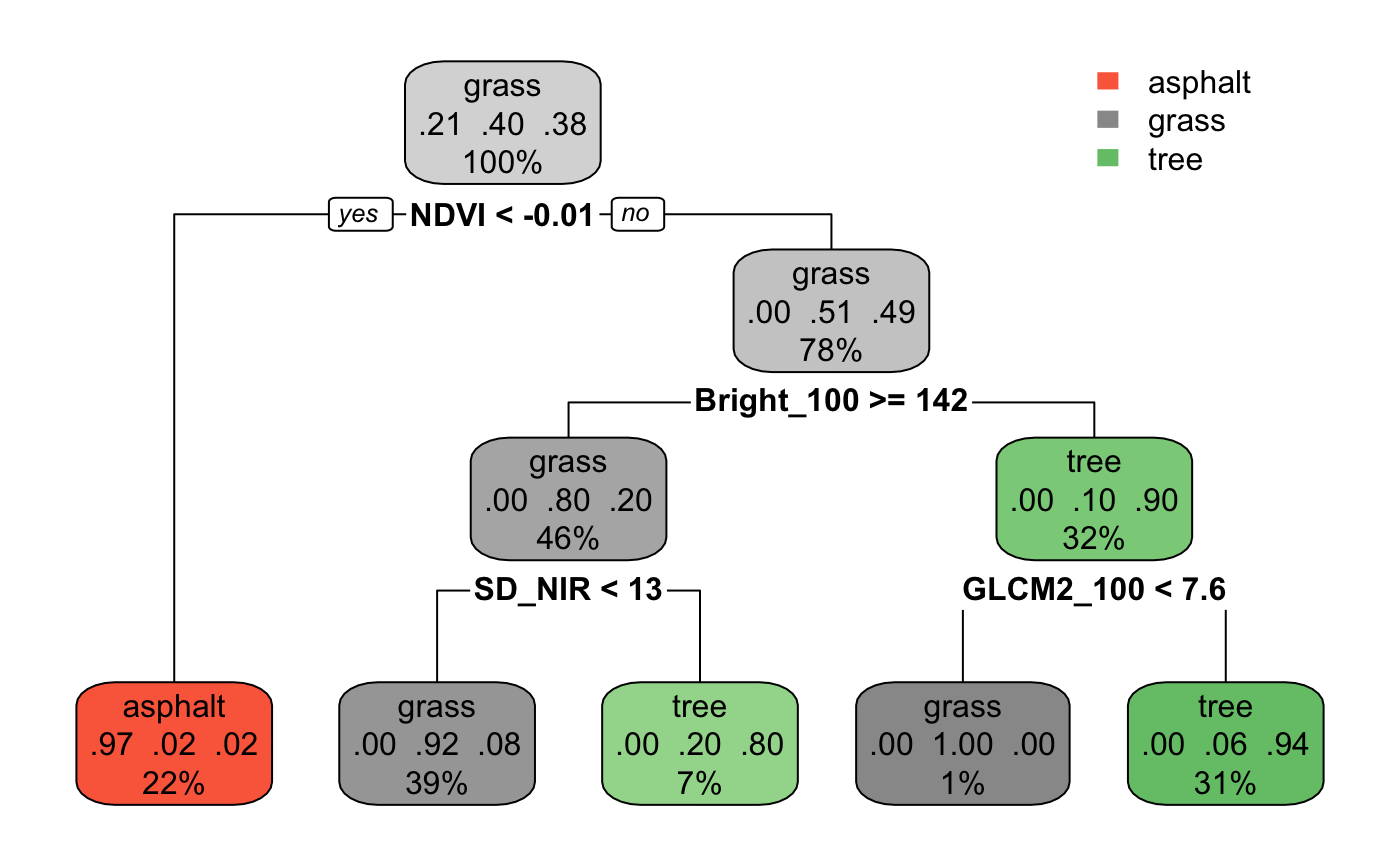

To better grasp the idea of decision trees, below is an example a classification tree in R I’ve produced using code from Prof. Brianna Heggeseth’s Statistical Machine Learning class site using the Urban Land Cover dataset from the UCI Machine Learning Repository which contains data collected on the observed type of land cover (determined by human eye) and “spectral, size, shape, and texture information” computed from a given image.

Figure 5: This is an example of a classification tree for land types.

(Source: https://ajohns24.github.io/253_Fall_2020/random-forests-bagging-ensemble-methods.html)

The tree above was trained using data collected on textural and shape characteristics of photographs of land from our dataset, the codebook for which is available here. The variables themselves aren’t very pertinent, but they can be helpful to keep in mind when trying to see the metric by which the tree splits the data by. However, for ease of reference, here are the four predictors chosen by the decision tree above at each node:

- NDVI: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (spectral variable)

- Bright_100: Brightness (spectral variable)

- SD_NIR: Standard deviation of Near Infrared (texture variable)

- GLCM2: Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix

Take a look at the red, leftmost leaf node. If the condition at the branching point is true, we go left. If false, we go right. In this case, if NDVI is less than -0.01, the tree predicts that a case with such a value will be classified as asphalt. Notice that there are three lines of text within this node:

- Asphalt, which is the predicted class

- The predicted probability of the node’s classification: 97% for asphalt, 0.02 for grass and tree classifications respectively

- 22%, depicting the proportion of the cases from the dataset within this node.

Also notice that as we follow the tree down to its leaves, the regions become more homogenous in the classes represented than the original regions before the split, as seen in the second line of text in each node. We can see that for each class of land type, the predicted probability of the node’s classification either increases closer to 1.0, or decreases closer to 0.0 with each split. This is what we know as node purity, quantified by what’s known as the Gini index, or the impurity measure (not to be confused with the economic measure of income inequality). When a node is pure, or when most of the cases belong to one class, the Gini index takes a small value. When a region is impure, or when cases in a given node belong to different classes, the Gini index takes a large value.

3.3 Tree Pruning and Overfitting

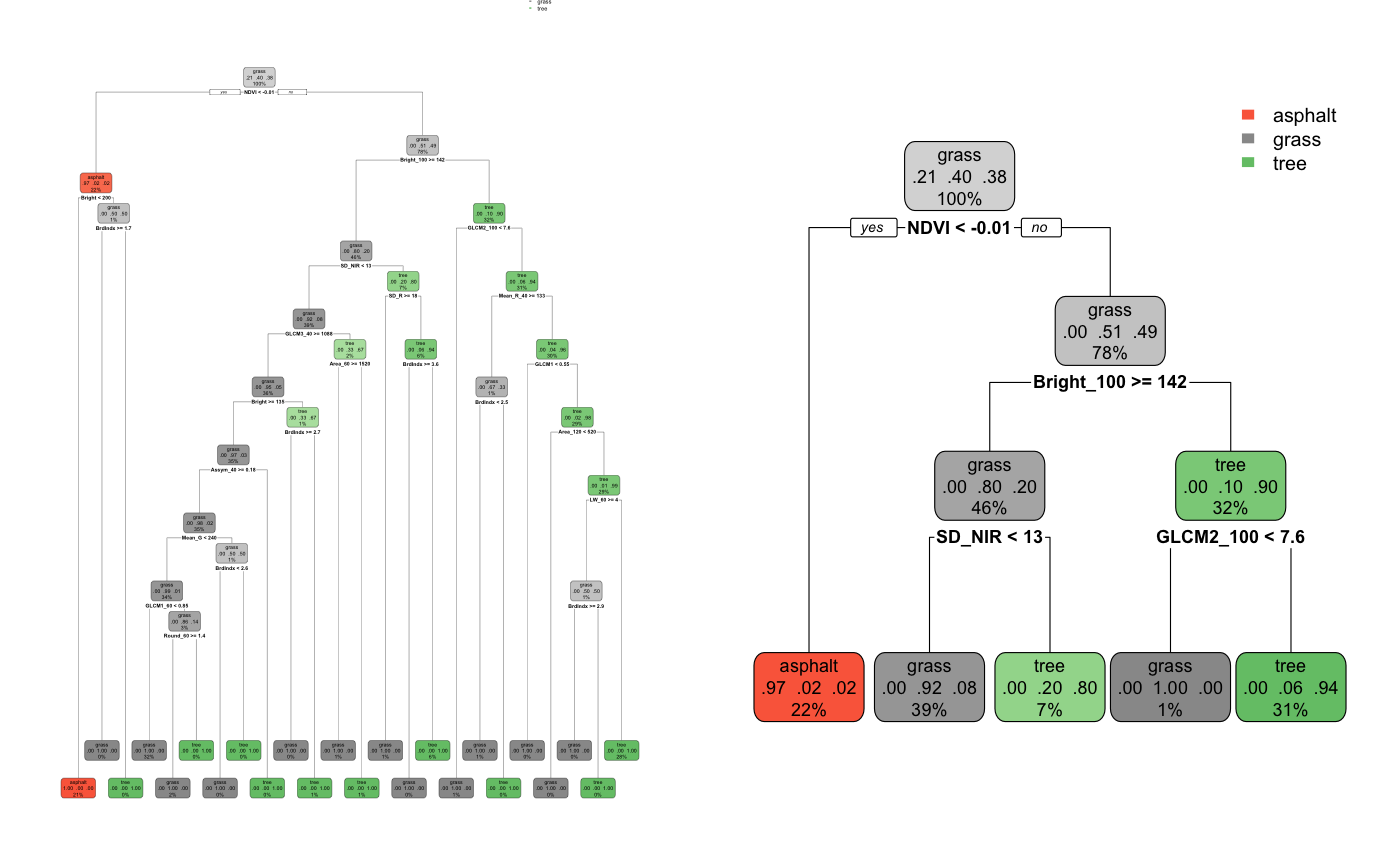

At face value, we can see that trees are fairly easy to understand, and you may have seen or used a classification tree at some point in your life. This is one of the greatest advantages of trees – that they are generally intuitive and easy to explain. However, one of the biggest disadvantages to decision trees is that they are high in variance, and thus prone to overfitting. The cost of the simplicity of a tree is instability. Classification trees are known to be a greedy algorithm, meaning that locally optimal splits in the data are made at each node, thus reducing its capabilities to produce globally optimal classifications. In other words, one of the decision tree’s fundamental flaws is that it does not know when to stop growing, or when to stop making splits in the data, which can result in an overfitted tree.

Figure 6: On the left is an example of an overfit tree. On the right is this tree, pruned.

(Source: https://ajohns24.github.io/253_Fall_2020/random-forests-bagging-ensemble-methods.html)

An over-specific decision tree takes away from its role as an algorithm by reducing its replicability/generalizability. With any algorithm, our goal is to take new data and run it through our algorithm which has been created and trained on existing data. The tree on the left of Fig. 5 is an example of what might happen if the tuning parameters are too loose – it will make decisions on splits in the data which are overfit to the data that was used to train it, thus poorly generalizing to new data. So, running a case through this tree will likely result in an inaccurate classification. On the right, is a “pruned” tree. The pruned tree provides looser parameters by which splits are made, resulting in a smaller tree. Though more generalizable, a smaller tree can fail to capture big-picture ideas from the dataset – small changes in the data can result in a large change in the final estimated tree.