Chapter 5 Application of Random Forests in Local Ancestry Inference

5.1 Toy Data Generation

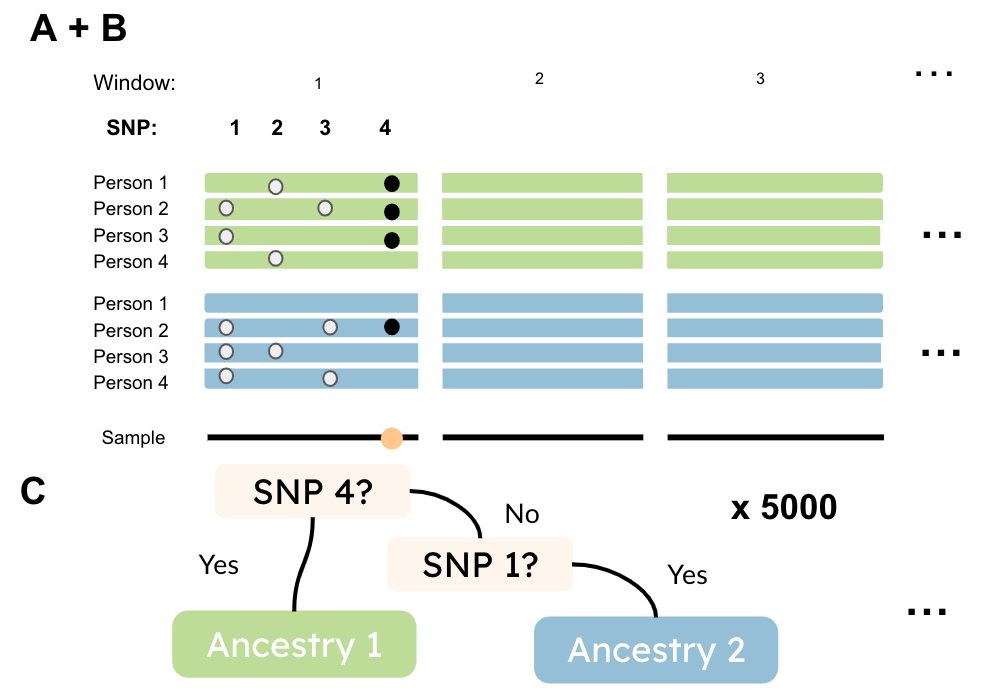

The random forest algorithm can be applied to genetic data to infer local ancestry by building and training a model on data where individuals’ ancestries are known. As shown in Figure 9, a data set can be constructed containing SNP MACs of various individuals known to come from different distinct ancestry populations. The SNP columns can be divided into local windows, each of which can be fed through the random forest model separately. The trees in the algorithm will ask questions about the MAFs of individuals in the given window, making splits based on the SNPs that demonstrate the greatest differences in MACs between people in the different ancestry groups. The many trees will each make splits based on these questions, and a bootstrapped aggregation of all of the trees will constitute a means for classifying any individual’s ancestry within a given window. This allows for a “painting” of each window of people’s genomes with the local ancestry inferred by the algorithm.

Figure 9: This image depicts how genetic data with known ancestry is organized, as well as how decision trees are used for classifying these ancestries. (Source: Freddy Barragan)

In order to demonstrate the algorithm in action, we constructed a toy dataset intended to represent one window of the genome of 1,000 individuals from two different ancestry populations, with 500 observations assigned to each group. To constitute our window, we used the rbinom() function in RStudio to generate MACs of 0 or 1 for 4 SNPs of interest and 26 noise SNPs, comprising a total of 30 variables. The SNPs of interest contained MACs generated from different rbinom() frequencies for people in each of our two populations, with the intention of these being important predictors for a decision tree classifying the populations to split on. The noise SNPs were generated using the same rbinom() frequency for all 1,000 observations, with the intention of these being variables that would hurt the accuracy of a tree forced to split on only a random subset of predictors.

We then used the caret package in RStudio to train a random forest algorithm on our toy dataset. We used the default settings in caret to create a model with 500 trees to classify our ancestry populations, and tuned the variable subset size to range from 1 to 30 predictors. We set up the algorithm to select the model with the variable subset size that maximizes out of bag accuracy as our final choice. Our hope was that the model would correctly pick out our SNPs of interest as the best predictors to split upon, and that out of bag error estimates might give us an idea of how accurately a random forest model might classify something like local ancestry in the presence of noisy data.

5.2 Random Forest Results

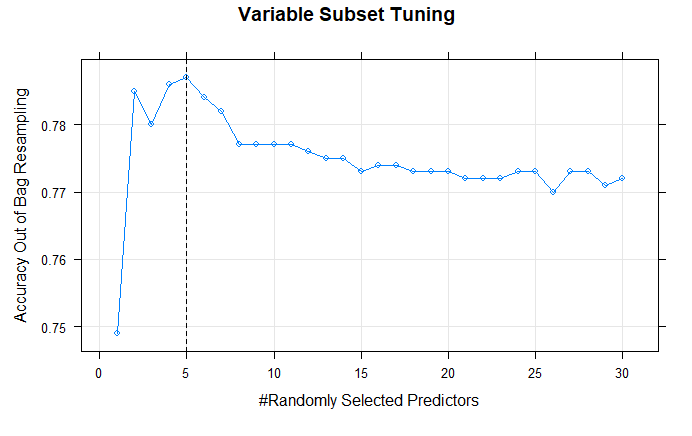

Figure 10: This plot shows the out of bag accuracy of the random forest algorithm with variable subset sizes ranging from 1 to 30. The optimal fit is with 5-predictor subsets.

The final model chosen by our random forest algorithm was one with a subset size of 5 predictors. As shown in Figure 10, a size of 5 predictors maximized the out of bag accuracy. This optimal subset size is what the model deems sufficiently large to ensure our SNPs of interest are considered often enough for splits, and also sufficiently small to ensure enough decorrelation of the trees before bagging. By contrast, the models tuned with less than 5 predictors would be considered underfit and high in bias, and those with more than 5 would be considered overfit to our data and high in variance.

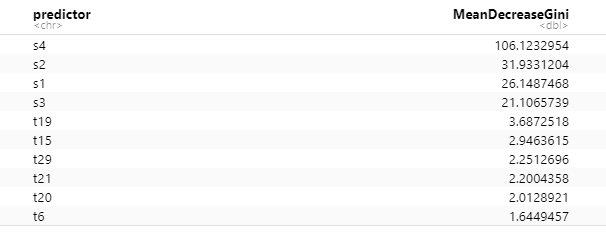

Figure 11: This table lists the top 10 SNPs in terms of split importance. It includes our 4 SNPs of interest labeled with s, and 6 noise SNPs labeled with t.

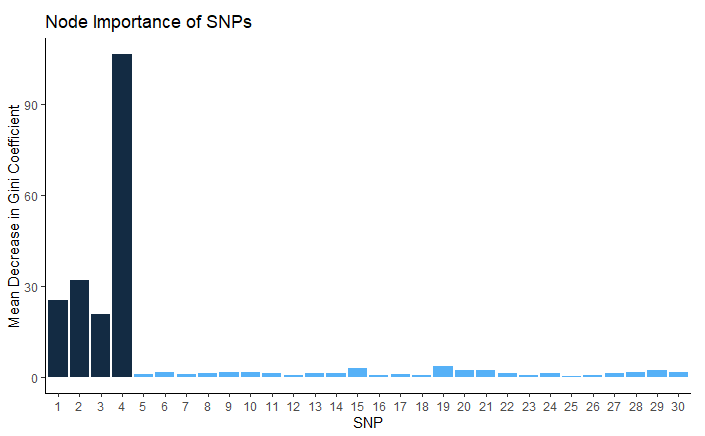

Figure 12: This plot shows the mean decrease in the Gini coefficient achieved by each SNP as a predictor in our model.

Figures 11 and 12 illustrate the importance of each SNP in our model as a split node, defined as the mean decrease in the Gini coefficient for each predictor across all 500 trees. As we had hoped, our 4 SNPs of interest stand out as far more important predictors to split upon than any of the 26 noise SNPs.

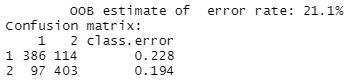

Figure 13: This is the confusion matrix detailing how many of the 500 observations from each population our final model predicted correctly and incorrectly, as well as an overall error estimate.

Figure 13 presents the overall performance of our final model. The confusion matrix tells us that this model produced an out of bag error rate of 21.1%, predicting 789 of the 1,000 total observations in our dataset correctly. Considering the inclusion of 26 noise SNPs in our window, our random forest algorithm did a relatively good job of predicting ancestry accurately.